Don Winslow took the scenic route to success.

He began his writing career in the early 1990s, and it wasn't until 2005 that he gained significant recognition with the release of "The Power of the Dog" — the first of his cartel novels. In total, he’s the author of over 20 crime novels and has sold millions of copies worldwide.

I’ve long been fascinated by his story, but recently I decided to go fully down the rabbit hole and learn everything I possibly could on how he actually writes. I’ve spent hours watching interviews, reading news articles, and listening to podcasts, taking notes and trying to piece together his path in a coherent way.

QUICK BACKSTORY:

He grew up near Rhode Island.

He worked as a movie theatre manager, a private investigator, and a safari guide.

He was an overnight success in his 50s.

If you’re brand new to Winslow, I’d start with The Cartel (2017) or City on Fire (2022), but he has a new one at the moment and it looks like this:

HOW DON WINSLOW WRITES:

Winslow doesn’t shy away from questions about his writing process. He’s not a writer who tries to hide this stuff away. So, there are clues out there about how he operates.

Here’s a distillation of what I could find out:

1. He writes without extensive notes or outlines to allow for surprises.

In one of the interviews I watched, Winslow claimed that his best stuff is his most off-the-cuff. He sometimes starts with titles or sentence fragments: the idea for one of the novellas in "Broken" came from the phrase "crime 101" coming to him as he drove down Highway 101 in California.

He is said to often have multiple projects on the go, but I suspect these are just long-gestating ideas floating around in his head, or research interests/projects.

2. First drafts are for self-entertainment, later drafts focus on the reader's experience.

Pretty standard advice, but I included it because leverages three other aspects of his work that all work in unison:

It plays into working without an outline, essentially forcing himself to be entertaining, beat by beat. His work reads like that. His prose style borders on miminalism at times, but Winslow as a real eye for melodrama. Lots of incident and plot. Lots of mayhem. His work is loud, and it makes sense that this is might be the byproduct of constantly thinking, what next?

He takes on a lot of editorial advice. Don Winslow is not reluctant to take notes from various people, believing that accepting feedback is essential to creating high-quality work and that feedback from trusted sources can help him maintain perspective on the work.

He edits with an emphasis on pacing. It gets granular here: for Winslow, pacing is achieved by the density of the prose on the page, and the negative space around key words or images. He acknowledges that the addition or subtraction of a single syllable can change the pacing, rhythm, and impact of the story.

There’s a great passage in this interview where he expands on that last point:

“The other goofy thing I do is I sit or even stand back from the computer screen so that I can see the shape of the words but not the words themselves. Then I ask myself, “Does it look like what it is?” If it’s a sequence where I want to grab the reader and not let the reader go then it needs to look dense. But at times I want the reader to focus on a certain word or a certain image and pause there, and then I need a lot of white space around those words or images so that there will be a little space for that image to exist.”

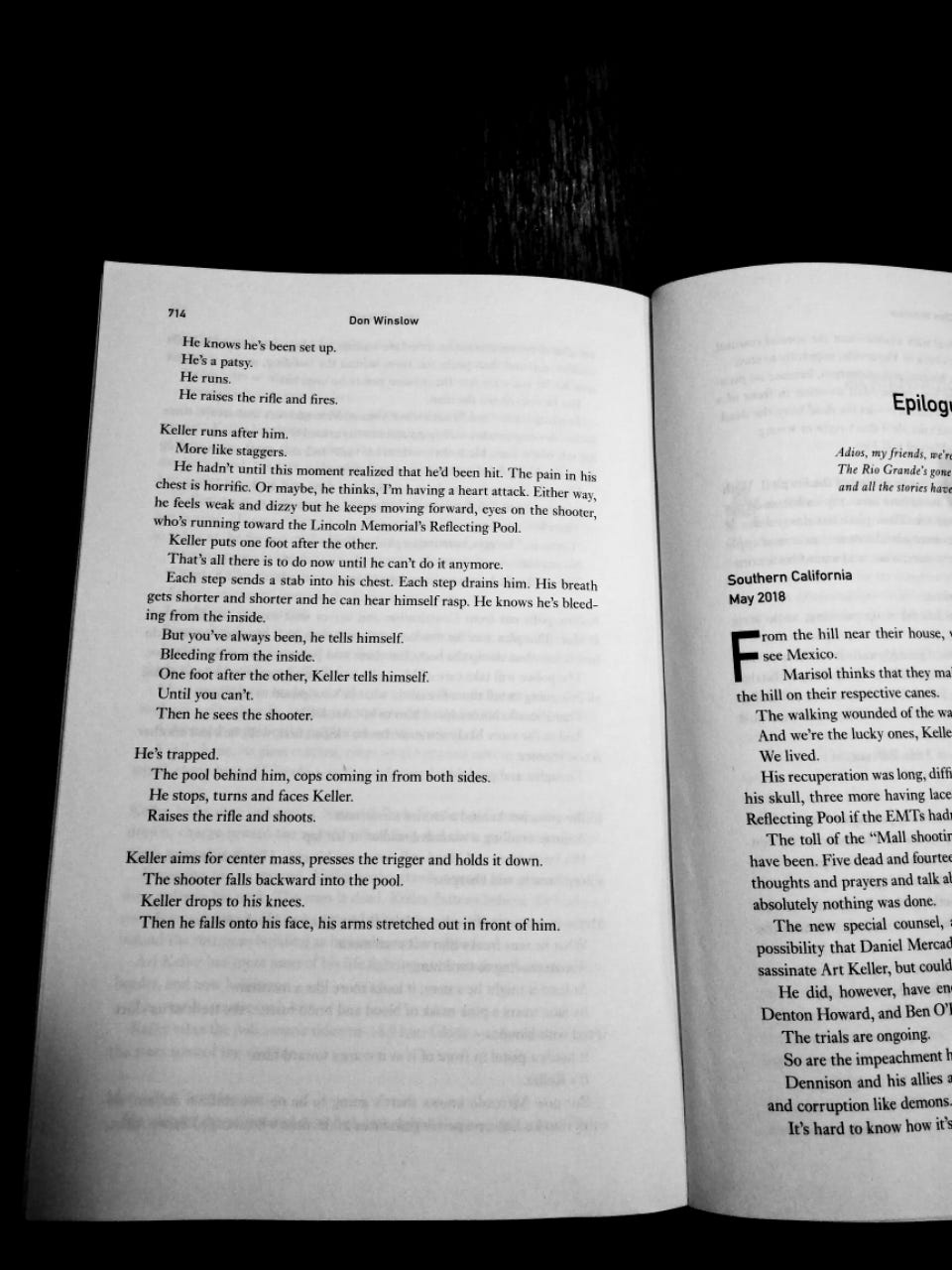

To illustrate, this is the final shoot-out in The Border (2019). Looking at it, you can sense that its action, rather than revelation:

It’s a great tip.

So while Winslow might be writing without a net (no outline), he’s focusing on keeping the story moving, then editing extensively on the back end. That’s not exactly what people think of when they hear about an author turning out a "messy first draft". There’s a bit of structured process there.

3. Start Early, Start Often

There’s a bit of chatter in his various media appearances about when he writes (the mornings, early) but when the Financial Review asked him specifically for craft advice, he defaulted to a technique used by a lot of super-productive writers: write often.

Look, if you can carve out an hour, great. But if you can’t, don’t worry – find half an hour, 15 minutes, or 10. The point is that you commit to it and do it. It’s better if you can do it on a regular schedule, but if you can’t, it’s all right. “Catch as catch can” is still caught.

His Influences:

These are the names that kept cropping up:

Raymond Chandler

Charles Willeford

Elmore Leonard

James Crumley

Joseph Wambaugh

John D. MacDonald

James Ellroy

Ross Mcdonald

He’s definitely a crime fiction guy, through and through. He’s big on hitting the classics of the genre.

What I Couldn’t Dig Up: Chapter Design

The one thing I can’t work out is how he structures his chapters in the Cartel books. He uses long chapters in that trilogy — with roving POVs — and they really work. But for the life of me, I can’t see how he demarcates them. The choices don’t seem arbitrary but if I had to guess, I’d say that he simply closes out a chapter after a climax or some sort. It also wouldn’t shock me if he writes the stuff as one long blast and inserts chapter breaks afterward, just for purely structural reasons.

What did I miss? Send me some links!

That’s all.

— IAIN

👁 Like the vibe of my newsletter? You’ll love my books 👁

PS: Read my public-facing thoughts Twitter and see how I live my life on Instagram.

PPS: This newsletter is brought to you by No Highs by Tim Hecker. Best thing he’s made in years and already a favourite of 2023.

Ever since Power of the Dog I've loved Winslow but Frankie Machine, the Boone Series, Savages, etc. They've all been great. Plus, the short stories.

I wanted to comment because I did read an interview ages ago where he spoke about chapter construction for Bobby Z. He had a morning train commute of about an hour and wrote on the train and said he got into the habit of trying for a chapter a day and wrapping it up when he was 15-20 mins away from his destination.