Long Story: THE DEATH TWINS

"It was a long night, something to survive first and remember forever."

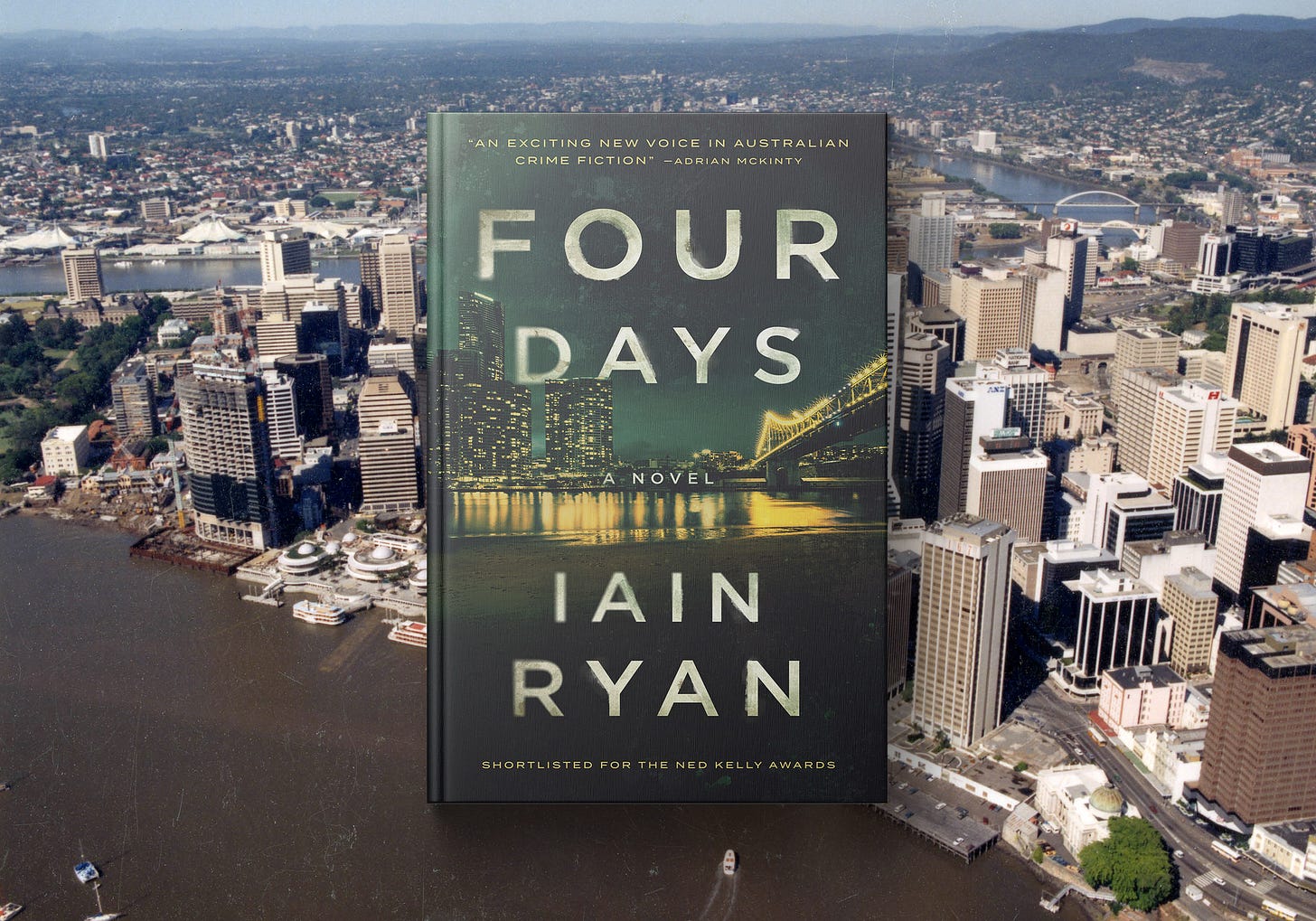

About a year ago, I reissued my first book, FOUR DAYS. It’s a pretty nasty little number and comes with a bunch of short stories. All of those stories, except for one, are from around the mid-2010s.

Today, I wanted to share the remaining story, which I wrote last year specifically for this edition. It was strange going back to this material, and even stranger slipping back into that earlier prose style (third person, past tense), but I’m happy with the result. It seems that, with writing at least, you can go home.

Trigger Warning: absolutely everything.

THE DEATH TWINS

Jim Harris watched the birds circle through the trees. They were sulphur-crested cockatoos, squawking and carrying on, oblivious to the rest of the world. Harris dropped his cigarette into the gravel and took another sip of tea. He was in the abandoned back lot behind the police station. It was usually quiet out here at dusk, but not today.

Harris took his gun out and trailed one of the birds.

“Bang,” he said.

But the little bastards kept flying.

*

Inside the police station, the DPU blokes were gathered around the kitchen table. Harris’s partner Old Bill Granger sat with them, holding a hand of cards. The room was full of second-hand smoke, and it was so thick that the TV set on the far wall glowed in the haze.

As Harris came past the table, Old Bill held up his empty stubbie. “While you’re up, son.”

Harris complied. He grabbed a drink for everyone because it was coming anyway. He knew the drill—Harris was still the new guy, even though he’d been on Tunnel Island for six years. There was no changing the DPU blokes, that’s why there were here. The DPU was where they sent the broken and useless coppers: the Displaced Person’s Unit. It was where the Queensland Police Force filed its dregs, when firing them was too difficult or too expensive.

In keeping with their regular hazing, the DPU blokes waited for Harris to settle himself on the couch in front of the cricket before one of them said, “Hey Bill, did you tell him about Chandler?”

“Chandler was looking for you,” said Old Bill. “Stuck his head in. Better go and see him.”

“He graced us with his presence,” said one of the others.

“What did he want?” asked Harris.

“Didn’t say.”

Harris rubbed his face. Bloody hell, what now? “Bill, what do you reckon?”

Old Bill cursed, but it was only at the card game.

“Bill?”

“What? Oh, I don’t know, mate. I’m in no state to drive, so if it’s important, you’ll have to handle it.”

*

It was important. Inspector Danny O’Shea wanted a private word. Harris drove up to the casino strip where O’Shea was holding court in The Pyramid Hotel. He was in the VIP lounge on the fifth floor, his bulk pressed into one side of a booth up the back. The man was squat and strong—a terrifying street copper in his day. Despite his standing on the island, O’Shea never dressed the part. Didn’t have to, because there wasn’t a club or hotel on Tunnel that would deny him entry. As such, O’Shea lived in shorts and polo-shirts. Today he had two men with him, both in dark suits. They made an odd party.

“Here he is,” said O’Shea. He turned to his guests and added, “I told you I was going to call the police.”

The other two men did not seem to find this particularly funny. The one closest to Harris fidgeted with his glass. Neither looked at him.

“Where’s your mate?” said O’Shea.

“Bill had an appointment.”

“Well, tell him to cancel his appointment next time, aye?”

Harris sighed. He dragged a nearby chair across to the table to avoid squeezing in beside O’Shea. “What can I do for you, Inspector?”

“My friends here have lost something, and they want it back.”

Harris opened his notebook. “Over here?”

“What do you mean, over here? Of course, over here,” said O’Shea. “Their car got nicked.”

“Oh, okay. Make? Model?”

The men looked at each other, then one of them said, “It’s a silver Mazda. The plate number is TFS 688. It’s the 1990 model.”

“Last seen?”

“It was pinched from outside this hotel,” said O’Shea. “About lunchtime today.”

“Security footage?”

“That’s where I’d start,” said O’Shea. “I want you to find it tonight.”

“It’s important,” said one of the men.

“He knows that,” said O’Shea. “If I tell him to do something, he’ll do it.”

Harris folded up his notebook. “I’ll see what I can turn up.”

“Good man,” said O’Shea.

*

The Head of Security at The Pyramid was a man they called The Fox. No one called him that to his face, of course, but that was his name, and nothing happened in the Pyramid without his say-so. He kept the place in line. The hotel was owned by Stanley Manning, some multinational company, and their day-to-day people were unruly. They got sent to the island from all over, like the corporate version of the DPU. Even The Fox—the guy holding it all together—even he seemed like a man who was being punished for something.

Harris called him from the bar.

The Fox was not impressed: “I’m trying to have dinner. What do you want?”

Harris told him about the car.

“Go down to the Security office,” said The Fox. “Have them call me back when you get down there. They won’t give you any trouble.”

Harris wasn’t expecting trouble. Tunnel Island policed itself, for the most part. Each of the major families had a private security team to handle their respective issues—rowdy guests in their casinos, the private foibles of staff, that sort of stuff—and thus the island’s official policing was about dealing with the rest, which wasn’t much. When it was all going well, everyone worked their own turf, and there was no real pecking order.

The night security manager at The Pyramid Hotel was a woman called Ruby. Ruby connected Harris up with her IT guy, and within the hour Harris found himself in front of the car park footage of the stolen car. On the screen, a man in a hat—a tan number with a long sun flap at the back—approached the silver Mazda, popped the door and got behind the wheel. A couple of seconds later he drove off.

“You recognise the guy?” asked Harris.

Ruby shook her head. “Did he even pinch it? That looked like he had a key, to me. If he broke in, he’s bloody good at it.”

Harris felt the same way. He wrote pro in his notebook.

Ruby noticed. “Do I get a cut of the reward now?”

“This is for O’Shea.”

“Oh.” Ruby knew the deal. With the Inspector, everyone worked for free. “You might want to try Gail down at the gates. This time of night she’ll run the plates if you bring her a carton of ciggies.”

“What does she smoke?”

Ruby walked across the room to a grey steel locker and retrieved a carton of Winfield Reds. She tossed the carton to Harris. “I’ll put it on your tab.”

“Reds by the carton, bloody hell. No wonder she’s so twitchy.”

Ruby laughed. “The sooner she gets the lung cancer, the better.”

‘That’s pretty rough, Ruby.”

Ruby gave him a look.

*

It was dark outside, and Gail was holed up in a little fart-filled demountable by the island’s entryway toll gates. These gates ran across the mouth of the tunnel, the maw rising up from the ocean like a giant beached serpent. Inside the demountable, Gail’s greeting was, “Get the fuck out of here, dickhead. I’m busy.” Busy meant eating a meat pie under bright neon lights.

Harris sat down across from her.

“What? You deaf and stupid?”

Harris said, “You know I’m a copper, right?”

“Oh yeah, a regular fucking Sherlock Holmes, you are.”

Harris placed the smokes on the table. He slid a piece of paper over beside Gail’s meat pie. The plate number.

Gail looked at it, shrugged.

“Thanks,” said Harris. “I need it ASAP.”

“I need someone to kiss my arse, ASAP.”

“O’Shea is the one asking.”

“He’ll do. Tell that big boy I’m ready when he is.”

Harris shook his head. Lung cancer would be a blessing if O’Shea ever caught her talking like that.

*

Harris circled back and picked up Old Bill from the station, and the two of them drove around. Bill hated the side-work for O’Shea, but he was years into it and didn’t have the pull to escape the arrangement. “I’ve gotten used to the money and now the money’s gotten used to me,” he once said, deep into a bender. These days it was almost as if they’d switched places: Harris took the orders and followed the leads. Bill was just along for the ride.

So far, their night searching for the missing Mazda had been uneventful.

A drive down the unpaved road behind Robinson Beach.

A whip around Point Burgess.

Bluewater Cove.

Then a slow winding tour of the casino strip’s various basement car parks, back lots and side streets. The only action down there was a chance sighting of Mister Bag, a local idiot who insisted on jerking off in public, emptying himself into a plastic shopping bag, hence the name. Mister Bag never went near people while he was doing the deed, and Harris was sick of locking him up, so they’d taken to leaving him be of late. Bill had mentioned more than once that seeing the man was good luck.

Later they made a quick trip into Domino to put the word amongst the various bikie chop-shops down there. Domino was Doomrider turf, but Bill still had a half-decent relationship with Vic Bishop, the head of the bikies, so they were allowed in for the night. Not that it produced much; a lot of blank stares and shrugs. Harris wasn’t sure they’d call if the car did pop up.

From there they hit all the safer spots—

The construction site in Silver Village.

Empty.

The suburban streets of Arthurton.

Asleep.

All that was left was the southern end of the island.

“Fuck that,” said Bill. He was out of booze. A half-dozen empties rolled around the Landcruiser floor by his feet. “Tomorrow. Can’t face it tonight.”

“O’Shea wanted this seen to,” said Harris.

“We’ve seen to it.”

“He won’t be happy.”

“Good.”

Harris turned the car around. In truth, he didn’t want to go any further either. The only place left to check was Drainland—the absolute pit of hell down on the southern tip of the island—and the rest was bushland and sand tracks. Real muck work, full of nightmares in the dark like this. No one went near any of that at this time of night, not even the police. A badge and a gun meant absolutely nothing down there.

*

The following morning, Harris and Bill had breakfast at the Arthurton bakery. It was a beautiful day—cloudless and dry—but Old Bill wasn’t feeling it. “I’m rostered off,” he said, which was true, but Harris figured his hangover was the main issue.

Harris wasn’t feeling great, either. He’d sweated through the night, tormented by bad dreams and ghosts. For some reason this thing with the car and O’Shea worried him. O’Shea didn’t tend to call them in for the little stuff.

“What would you be doing at home anyway, Bill?” said Harris. “You got hobbies I don’t know about?”

“I had a day planned.”

“Pulling your dick isn’t something you need to plan out, is it?” said Harris.

“It is at my age.”

“You ever think about fishing, or I don’t know…”

“I’ve thought about it,” Bill said. You could see the water from his fibro shack. “I just, I can’t see the point of it, I guess. You do what we do for a living and catching fish feels a bit bloody light on.”

“Lawn bowls, then?”

“Fuck off.”

“Maybe you could retire?”

“I am retired,” said Bill. “We’re both retired.”

It was true, in a way. There wasn’t much separating Bill and Harris from the DPU blokes. It was all much of a muchness.

“Come on,” said Bill, getting up. “Let’s get this over with.”

*

If Tunnel Island was where the dregs of the mainland ended up, Drainland was home to the dregs of the dregs. It was the bottom of the funnel, a sprawling beach encampment on the beach populated entirely by the drug-addled and insane. Every type of vice existed there, totally unregulated. The police didn’t go in. Likewise, the Agriolis family and Stanley Manning wanted no part of it either. Only the Doomriders were directly involved: they supplied the place with narcotics—and kept the peace, occasionally—but Harris heard they rarely visited the camp itself, not unless there was a real emergency. In short, everyone stayed well clear.

The outer boundary of the camp was marked by a bluff of black, volcanic rock and that’s where the road stopped. There, in a basin of beach sand at the base of the bluff, sat two dozen cars in various states of disrepair. Some were relatively new additions (sagging tires, salt-encrusted and immobile), while others were rusted shells, windowless and open.

Bill stayed in the car, hand on his gun—keeping watch—while Bill checked the number plates.

It was a bust.

“It’s not here,” Harris said.

“Come on. Let’s go.”

Harris trundled back through the hot sand. He was hoping they’d find the silver Mazda, if only because visiting this place came with a toll. All the broken cars, parked on a broken promise. A day or two in Drainland, that’s all. And all of them thinking the same thing: that they could visit without slipping into the void, go down there and come back without forgetting how they got there.

*

Not far from Drainland, Bill told Harris to pull over. He pointed to a roadside house in the scrub, a single-story brown brick. “Let me introduce you to someone,” said Bill.

That someone was Chris Mason, an old Darumbal bloke, weathered and grey. Harris had heard of Mason, specifically that he lived down here somewhere. He was a poet—a big deal in the straight world, back in the day. Tunnel seemed like a strange place for him, but here he was, sitting out on his veranda eating a bowl of Weetbix. “What are you two after?” he said as they came in.

“Chris, this is Jim Harris.”

Harris gave him a nod.

“Yeah, okay,” said Mason. “What do you want?”

Bill planted himself in a plastic chair beside Mason. “We’re looking for a stolen car.”

“And you reckon I stole it?”

“Can you drive?”

“Nah.”

“Didn’t think so. You ever worry about what’s going to happen to you out here if you get into trouble again?” Bill hooked a thumb at Mason. “This idiot had a heart attack a couple of years back and had to crawl out onto the road to get help.”

“If I die, I die. Who gives a shit?” said Mason, lighting a smoke. “Not like I’ll be around to see it.”

“That’s why I’m here, actually,” said Bill. “You still writing your limericks out here on the veranda?”

Mason shook his head.

Bill pressed him. “You see a silver Mazda sedan come past in the last day or so?”

“Nah.”

“You sure?”

“I don’t know.”

“Fuck me,” said Bill, shaking his head. Turning to Harris, he said, “You got any cash on you?”

Harris handed over a twenty and Mason laughed as he took it.

Mason said, “No silver Mazda or anything like that. But there were some headlights up there last night. Turned down the next road up. Bit bloody odd. No one goes down there since they closed the plant.”

“Anything else?” said Bill. “That’s not much for a twenty.”

The man looked at him and said a few lines of poetry.

“Yeah, okay,” said Bill. “You write that?”

Mason shook his head. “I don’t write anything anymore. I just sit here.”

*

Up the road from Mason’s house, there was a gravel track that took them deep into the bushland, past the rim of a white sand basin formed from the dry remains of a lake. Around the edge of the basin, the track came to an end with a gate running across. It was an old sewerage plant, and there, parked in front of the gate, was the missing Mazda.

“Thank Christ for that,” said Bill.

“Looks dumped,” said Harris. “I’ll call O’Shea.”

But Bill noticed something. “Hold on,” he said, and stepped out of the car. Bill squatted by the rear boot and pointed to a dark smear on the paintwork. “That’s blood.”

Harris wandered alongside the car, checking the windows. It looked clean, empty, like a rental. He opened the driver’s side door and popped the trunk.

Behind Harris, Bill made a strange sound, something halfway between a gasp and a shout. Harris watched him stagger back and heave, Bill’s body expelling breakfast with a horrible cat-like sputter.

“What? Wha…” stammered Harris, as he came forward.

“No, don’t,” said Bill, his arm up, as if trying to wave him off. “Stop.”

But Harris didn’t stop. He looked in the trunk, and the moment he saw the body he knew he’d be living with it for the rest of his life. It had once been a man, but his remains were cut up and placed in clear bin bags. It wasn’t so much the body parts or the blood congealing around them—Harris had seen plenty of that—it was the arrangement of the thing. Parts of the torso were positioned below the legs, with the face, gagged with electrical tape, wide-eyed in terror, was pressed against the man’s own open waistline, separated only by a thin veneer of plastic.

“Jesus fucking Christ,” said Harris.

“Shut it up,” said Bill. “Can you please shut it up?”

Harris closed the body back in. He lit two cigarettes and gave one to his partner. “I better call O’Shea.”

Bill straightened up and took a long drag. “No.”

“No?”

“Hold on a sec.”

They smoked in silence.

“Bill?”

“Okay, okay. Let’s go see the shithead.”

*

Inspector Danny O’Shea wasn’t in the mood for a chat. Harris and Bill’s visit had interrupted the end of a televised cricket match, a close one between Australia and England. “Come on, you wankers,” hissed O’Shea, eyes on the TV over Bill’s shoulder. He turned back to them and said, “He was what?”

“Cut up,” said Harris.

“In the Mazda?”

‘That’s right.”

“I don’t suppose you recognised the bloke?” said O’Shea.

Harris handed O’Shea a polaroid photo of the body.

O’Shea was watching the TV again. He pulled his eyes away from the screen, looked at the photo—drew it in close—and shrugged. “Fucked if I know. What did you do with him?”

“Left him there,” said Bill. “Who came to you about this?”

“You met them,” O’Shea said to Harris. “Americans, I think, or Canadians. I can never bloody tell. They had some pull with Stanley Manning. That’s how we ended up with it.”

“You think they killed this guy?” said Harris.

“I fucking hope not,” said O’Shea.

“Give us their names,” said Bill.

O’Shea couldn’t recall their full names, but he knew they were in staying in the Western penthouse of The Pyramid.

“What do you want us to do?” Harris said.

“Fix it. Come on, goddamnit.”

Harris didn’t flinch because the last part was about the cricket.

*

Over at the Pyramid, a security guard let Harris and Bill into the penthouse. The suite was still booked, but the men were long gone. “All their clothes are in here,” Bill said. “And I found this.” He dropped a stack of cash on the coffee table. It was a fat wad: five figures, held together with a rubber band.

“What do you reckon?” said Harris, nodding at the money.

“Leave it for now.”

The two detectives took a walk down to the security office in the basement where they met with a computer guy who looked after the key card access. He told them the penthouse was last opened early that morning.

“Can you pull the footage?”

“Not without a warrant.”

They were always cagey about surveillance in the buildings on Tunnel; the whole place ran on privacy and discretion. But Harris knew the workarounds. He said, “What about the basement car park for the hour after that door was opened? I need a read on what car they drove out of here in, and then I’m out of your hair.”

“Can I call Ruby?”

“I’ll call her,” said Harris.

They got the footage. Harris and Bill watched it on jog-shuttle and smoked cigarettes. It didn’t take long—fifteen minutes in, Harris pointed at the screen. “There.”

Four men, stepping out of the basement elevator. Two of them were the suits from the meeting with O’Shea. The other two were dressed in identical tan hats, both with the long flaps at the back, and both in black sunglasses. One in front and one following behind.

“One these blokes stole the Mazda,” said Harris. “He was in the footage from before.”

Bill leaned in close to the screen. “The other two look scared.”

“Yeah,” said Harris.

They could feel the bad energy of it flowing. They both knew that more bodies were going to turn up.

“Let me switch over to the front gate,” said the computer guy.

Two minutes later, they watched the men drive up the ramp of the carpark in a white van.

*

Back to cruising the island. Harris called in the van’s plates, make and model. At the station, Constable Denny O’Connor was on duty and getting amongst it. O’Shea put the word out with the families and business owners—it wouldn’t be long.

An hour later, the sun set and the island did what it always did. The bright parts got neon bright, and the rest turned pitch black. That’s when the call came. A white van had been spotted out the back of an industrial shed down in Domino. Some of the Doomriders were making to pinch it, but were smart enough to run it up the chain first.

“Two trips into Domino in one week,” Bill said as they turned off the main drag. “One for the books.”

The tip-off checked out—a run-down shed. Looked abandoned, except for a dim light inside. The white van was still in the lot behind, as reported.

“What do you reckon?” Bill asked.

“Let’s go—”

Harris was interrupted by a short whistle.

Both of them turned.

A man stood on the empty street, holding a shotgun on them.

Before they could move, a soft voice came from the other side of the car. “Uh, uh, uh.” Another man with another gun. He came up to the driver’s side window and peered in. “You looking for us?”

Harris and Bill stayed quiet.

“We could use a hand,” said the one by the car. “Come on. Out you get.”

The interior of the shed was empty, bar a gas camping light and the bodies of two men. These were presumably the two from the Pyramid, both sprawled out on the ground, bloody and naked, their hands cuffed to adjoining posts.

“Are they dead?” said Harris.

“I hope so,” said one of the armed men.

In the light, Harris could see them better. They were the men in tan hats from the surveillance footage. With their hats removed, Harris could see that they were twins. Two big, blond identical twins, clean-shaven and muscular.

“I can handle these two,” said one of the twins.

The other stepped out back, towards the van.

“What’s this all about?” said Bill, inspecting the bodies. “These two don’t look like crims.”

“They’re lawyers.”

Harris found himself getting anxious. The armed man’s demeanour was off. His voice was calm, almost robotic, and though he looked at them as he spoke, his gaze carried no emotion at all. Harris had seen corpses with more charisma.

“Well, they were lawyers, I guess,” the man said.

“Who’d they work for?” said Bill.

“I don’t know. They didn’t end up here because of that. These two, and the other one, they drugged and gang-raped a sixteen-year-old girl in Sydney. Her parents remortgaged their house to hire us.”

Harris and Bill exchanged a glance.

“What are we going to do now?” said Harris.

The man waved Harris forward with his gun. “You grab his legs. Your friend can get the arms.”

The man retreated into the shadows and returned with a box of plastic bin liners. Then his brother returned from the carpark with a rotary bandsaw.

*

The twins let Harris and Bill live, but it was a long night, something to survive first and remember forever. The unspeakable horrors of the bandsaw—specifically the sound of the saw at work—gave way to a quiet drive down to the southern end of the island, back to the road by Chris Mason’s house and through the bush to the Mazda and the first body. They slopped the body parts into the back seat of the car. When it was done, the four of them drove the van and the Mazda out onto the dry lakebed adjoining the road and set them on fire. Out there, in the blaze of peeling paint and glowing metal, the twins stood and watched. One of them took a Snickers bar from his pocket and ate it, as if this were any other night.

*

Old Bill quit the next day. He went back to the penthouse of the Pyramid and took the dead men’s money, then told O’Shea he was done—no more extracurricular work. “You can fire me off the Force if you like.”

O’Shea was unimpressed. “Bill, you always were a soft bastard,” he said, flecks of beer foam spraying from his mouth.

Bill didn’t respond.

“And what about you?” said O’Shea, looking to Harris. “Are your panties in a bind over a couple of dead rapists?”

Harris shrugged.

Bill got up from the bar. “Inspector.”

He walked.

“Don’t worry about him. He’ll be back,’ said O’Shea. ‘That dumb prick can’t hold onto a dollar for long.” He signalled the bartender for another. “You’re not thinking about a drink, are you?”

It was another dog act from O’Shea. Harris had been sober for a couple of years. He went to the meetings, had the tokens, the whole bit. And no, Harris wasn’t tempted. In fact, he felt the opposite. He felt good, somehow. He knew he’d come face to face with something dark. He had communed with pure evil, something of that order. But instead of recoiling in horror—or running terrified towards drink and drugs—Harris experienced a strange sense of calm.

A stillness overcame him.

“Suit yourself,” said O’Shea, slurping on his beer.

Harris stared into his reflection across the bar.

The two of them.

Harris and Harris.

Like twins staring into each other’s eyes.

END

FOUR DAYS is for sale now:

Cheers,